Dr. Agnes Kalibata, UN Special Envoy to the 2021 Food Systems Summit

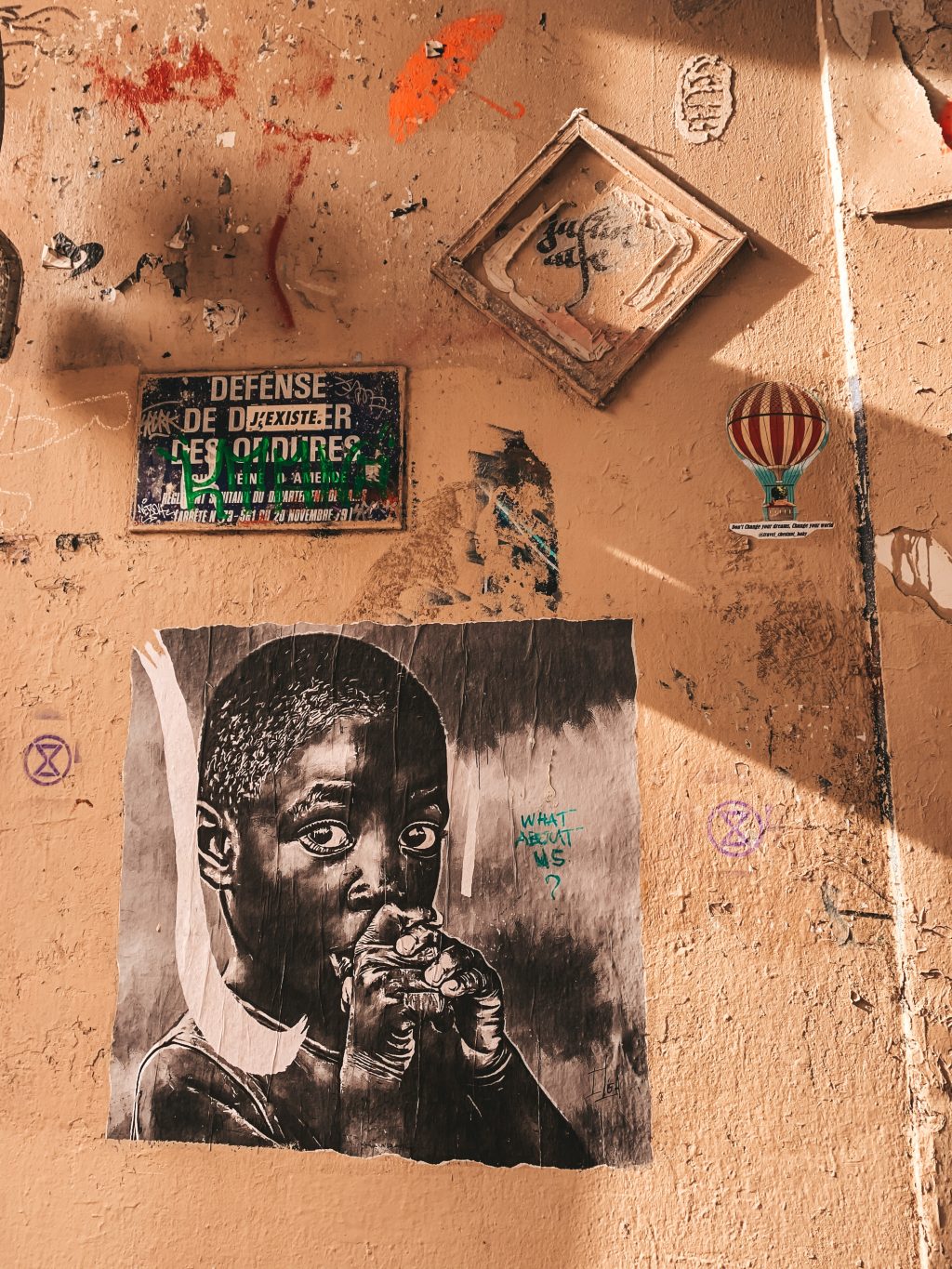

People living on the verge of crisis are often invisible until a shock hits, as COVID-19 has so alarmingly shown us.

Seeing what lies ahead is no easy task. It is difficult to predict who will be made vulnerable by different shocks, something we are witnessing all too clearly now, as millions who had previously managed to put food on the table are likely to be pushed into extreme hunger this year.

But if hindsight from these recent tumultuous months has taught us anything, it is that leaving huge populations to get by in life on the smallest of margins means that shocks have devastating repercussions. Investing in greater food security will provide a critical buffer against such events in the future.

Admittedly, identifying people living on the edge of food and nutrition insecurity is difficult, and events like COVID-19 complicate matters further, with each country, region, community and individual facing slightly different challenges.

Our current food systems are ill-equipped to provide healthy and safe food for all during ordinary circumstances, let alone when crises strike. But they also have enormous potential to be a safety net for vulnerable populations, as long as we act now to future-proof them.

Future-focused food systems could offer a solution.

Nutrition is a key outcome from well-designed food systems, underpinning everything from health to productivity and economic growth.

But the current systems we rely on expanded organically and haphazardly. They were certainly not designed to deliver nutrition to 7.8 billion people and counting – especially not the most vulnerable and those living on the brink.

With a growing global population, rising demand for food and increasing climate pressures, future shocks threaten to leave even more people behind.

Our future food systems must be both more accessible and more shock-proofed. Building better nutrition for all into these systems will provide the foundation for greater resilience.

To this purpose, the UN Food Systems Summit is not a singular event, but rather a process – under way now – that is geared towards understanding specific regional challenges and mobilising action towards finding the right solutions to make our future food systems more sustainable, resilient and inclusive.

Indeed, there is no one size fits all approach to tackling malnutrition or delivering sustainable nutrition for all. Both can only be tackled over time and with intention, through strategies that address specific needs and deliver localised solutions.

Firstly, we must identify and understand the needs of vulnerable populations.

To target programmes effectively, we need to take a step back and work out specifically who we are trying to help. Who is suffering from malnutrition now, and who will be at risk from future shocks? Where are they? How can they be reached? What can we do now to protect them in the future? These are some of the questions that will be posed during the regional consultations that will feed into the Summit.

It is only once we have identified where vulnerable people are and the specific challenges that they are facing, that we can begin devising localised strategies to support them with better food and nutrition.

Secondly, we need to design local solutions for local problems.

Where nutrition is concerned, both problems and solutions can vary hugely across countries, regions and communities.

For instance, in my time as Rwanda’s Minister of Agriculture, there were two major nutritional challenges facing the country: the extremely hungry who needed instant sustenance, and the farmers who were producing food but could not convert this into a healthy, sustainable diet for their families.

It was clear to our team of ministers that while both were nutritional issues, the solution to one would not work for the other. The extremely hungry could not be helped by agriculture alone; they needed social protection programmes designed around their needs, that also took care of nutrition. And the undernourished farmers often did not have enough land or crop diversity to provide sufficiently nutritious diets, or access to the right markets to make a living, so an entirely different form of support was needed.

Understanding and respecting these key differences in circumstances is crucial to designing effective solutions, which is why frequent regional consultations will be held to inform the Summit agenda.

Thirdly, we must track our progress in order to drive collective action and maintain momentum.

We all play a role in food systems, but those of us with the power to effect positive, transformative change must be held accountable to do so.

To ensure countries deliver on this transformation, we need measurable commitments from governments regarding food and nutrition, which can be reviewed and evaluated – similar to how Paris Agreement climate action targets are set out in Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).

Such a need for food systems action at a national level was outlined in a recent report, which found that more specific commitments from countries could also help mitigate climate change impacts and limit global warming. Our high ambitions of what we want to achieve over the next decade are laid out clearly in 17 specific global goals. Yet to reach them, we need to be more deliberate in not only securing country-level commitments, but also in identifying actions needed from the public and private sectors, including how cross-cutting issues of governance, finance, innovation and culture can be leveraged.

Recognising how we are all interconnected is key to this, as is differentiating between which countries have the ability and will to move things forward, and which need more support. Private sector actors have an influential role to play too, with the ability to take a stand and lead by example on environmental and nutritional issues, while public-private partnerships will be pivotal in laying the groundwork to make sustainable nutrition a reality for all.

This need to direct, coordinate and mobilise action on a global scale is why the Summit has launched five action tracks, designed to help shape commitments and outline essential priority areas for our future food systems.

With the empowerment of women and young people underpinning all five areas, they are a clarion call for collective action to build sustainable food systems that deliver safe and nutritious food, better livelihoods and resilience for all.

By driving and measuring the progress we are making on these action tracks through crucial mechanisms of accountability, we can build nutrition for all into the foundation of our future food systems.

That way, rather than weighing up the cost of our inaction when we get to 2030, we can talk instead about how far we have come.

Would you like to read more Insights like this one?

Sign up to receive the latest from the Futures Centre.

Join discussion