The pandemic has disrupted and reconfigured urban life. What is the potential for shifting to a people-first lens for urban transformation? Damiano Cerrone from Demos Helsinki and John Hadaway from SPIN Unit highlight and interpret the signals of change they are seeing.

Throughout history, cities have undergone a series of transformations that have radically changed the way we live, work, socialise and innovate. Transformations are rarely good to bridge the inequality gap of our societies, although urban change always mirrors societal change. However, the productivity boost we’ve been waiting for, for nearly 20 years – Google docs was first released in 2006 and Skype in 2003 – might now be at the doorstep, triggering a radical change in urban development and the economies of our cities. We are living through a fast-phased societal change triggered by the adoption of pervasive communication tech and a renewed recognition of wellbeing as a key driver of economic growth. With the stock market still growing and the deployment of mRNA technology enabling vaccination, it is quite likely that we are reaching the peak of this transition period, and tangible urban transformation will be visible once we exit lockdown measures.

If a spike in productivity has already triggered a new urban transformation, we are already late in preparing the much needed transition plans for a just and equitable change. The smart city as we know it is not the solution. The annual deployment of smart-city projects is in steep decline and Europe reached its peak already before the pandemic. Giants of the sector like Cisco System see less opportunity in smart city projects as municipal budgets are focused on the health crisis and to contain the economic downturn of COVID 19. However, already in 2019 Sidewalk labs’s CEO stated on Freakonomics Radio that “it’s hard to retrofit old cities for the 21st century lifestyle”. And perhaps this is the major caveat for smart city development. Only a few Nordic Smart Cities are managing to integrate socially relevant solutions in existing cities. At the same time, there is clear scepticism from the general population on data collection, data analysis and how this information is utilised in local governance for policy making. Overall, there is a sense that smart cities may not be the best solution to increase equality and spatial justice and a new development process is awaiting.

This suggests we might be entering a new urban transformation that is less focused on system efficiency and more on wellbeing; we’ll keep monitoring urban trends to study this phenomenon. But already now we are seeing clear signals of change, suggesting a new city making process is emerging. From a long list, here are 5 signals we’ve been monitoring more closely than other:

Going from in to of

Geoff Mulgan recently affirmed that we are in the midst of an Imaginary Crisis, a moment defined by a deterioration of our shared social imagination, by an abrading of our ability to beam positive yet tenable futures into a shared space of the possible. Taking Mulgan’s lead, we might, for a moment, turn to cities. In April 2020, just as the pandemic was beginning to uproot many of our lives, several professors argued, in The Lancet Psychiatry, that “a major adverse consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to be increased social isolation and loneliness.” With many of us resigned to our screens and pedestrian activity blunted, cities, engines of fluidity and sociality, became patchworks of discrete self-isolating homes. Social activities like graffiti, which, according to one Levebrian reading, might be read as a creative, intervening act that transforms increasingly commodified urban spaces into social spaces of belonging, became more peripheral. More than ever, perhaps, people in cities, increasingly isolated and lonely, might be feeling in rather than of; their position as a belonging member of the city, as a partial, transitory, affecting, imagining, graffiti-making participant in an evolving urban future, never more in doubt. The ability for people to speculatively intervene in our cities — to make their of-ness felt, to participate in the social imagination — is at risk, perhaps even, as Mulgan suggests, already in crisis. The onus is, in part, on cities to develop new forms of interaction, systematic methods in which everyone in cities — not just a few — can socially imagine and reimagine urban futures and, in the process, feel of the city, not merely in it.

Cities are collapsing into our homes.

Whipsawed by the pandemic, many commentators were quick to declare The Death of the City. The sense was, in part, driven by a flurry of data and reports, all signalling that urban churn rates were growing. As Reuters reports, a survey from November, run by Arup, suggests that some 59% of Londoners, 41% of Parisians, and 30% of Berliners considered leaving the city at some point during the pandemic. Indeed, to many, the pandemic occasioned a series of visible, lived transformations, transformations to which cities were slow to respond. On one level, this slowness represented a business opportunity, a problem to which surplus capital could be deployed, promoting new ways of urban life and urban personas of interconnectedness. Technology companies, not as inhibited by slowness, filled gaps in urban infrastructure accordingly, allowing people to collapse urban amenity-seeking into their homes and onto their screens. Uber’s recent acquisition of alcohol-delivery service, Drizly, for approximately 1 billion euros is indicative. On another level, slowness only exists if we imagine something as moving towards another thing slowly. The proximity of urban amenities to the home, which is increasingly central to work, play, and consumerism, has emerged as a design imperative, as something that cities should be moving towards — quickly, at that. This imperative is patent, for example, in the growing popularity of Ann Hidalgo’s Ville Du Quart D’Heure model. New visions of localness appear to be taking hold, rendering the home more central, as the place where assemblages of urban amenities should collapse digitally and — so long as they are no further than 15 minutes away by foot — around physically.

Increasing competition for intangible assets

Since 2008, New York City’s municipal government has adopted urban governance strategies favourable to the tech sector. Indeed, the response to the financial sector’s fallibility, plain in 2008, was to locate a new engine for urban economic growth, turning powerful, policy-making eyes to tech. As Sharon Zukin suggests, officials assumed dense, urban cultures of innovation to be productive forces, forces whose scalable, digital economic outputs could be captured by the city, creating jobs and fueling growth. This assumption was not unfounded. We see, for example, that density seems to be good at generating atypical ideas. Naturally, this assumption and the tech-enticing, culture-building strategy that it entails became widespread, far beyond NYC, before the pandemic. The pandemic, however, introduced new dynamics, ones that made competition over human capital between cities fiercer. Miami, for example, took advantage of the exodus from tech hubs like NYC, branding itself as the cryptocurrency capital. In March of 2020, just as the pandemic was taking hold across Europe, Hamburg and Cologne joined the SCALE.CITIES network, a partnership that purports itself as helping cities develop local cultures of innovation. To be sure, cities view tech as a boon and developing a culture of innovation — a healthy ecosystem — as a way of locally reaping its economic rewards, rewards that appear especially gainful during a crisis. And in a distributed world where the spatial form of an innovation district is not as vital, the playing field has, in many ways, been levelled, allowing more cities to rebrand, to aim at both developing a culture of innovation and increasing intangible assets (human, cultural, and intellectual capital). Last May, Savannah, for example, announced that it was willing to pay qualified technology workers USD 2,000 to relocate, taking steps towards rebranding itself as an innovation hub.

Moving beyond the rigidity of land use planning

Karma Kitchen, transforming industrial spaces into cloud kitchens, raised a EUR 302 million Series A round last July. On its own, that data is perhaps uninteresting, another expensive mark in a brisk history of venture capitalists deploying capital. A closer, contextualizing look, however, proves fruitful. As Business Insider reports, Karma Kitchen’s founders had, prior to the pandemic, only planned on raising EUR 3 million. Indeed, restaurants, shocked by the pandemic, turned to delivery, and Karma Kitchen provided a way, an adapted, private spatial form, for restaurants to access new delivery areas without taking on excessive capital expenditure risk, lessening the friction of distance. In turn, food delivery grew to account for 85% of Karma Kitchen’s business, imploring the company to partner with a private equity firm that deals primarily in industrial real estate, enabling them to raise the round that they did and plan to expand operations into other urban areas. Crises put our cities into motion, and cities in motion require flexibility. The success of Karma Kitchen’s business model of privately fitting-out spaces for temporary uses that were incalculable pre-crisis points, more broadly, to the importance of planning for flexibility, of moving beyond the rigidity of land-use planning.

Widening divisions in urban citizenship

Previously, we referred to the importance of creating systems for social imagination, facilitating a shift from in-ness to of-ness. However, inequality, a tacit question, was left unmentioned. The pandemic has intensified inequalities in the extent to which people feel of the city. Indeed, cleavages in urban citizenship are becoming more tangible. Globally, we see informal workers and the urban poor, already privy to less social protections, bearing the brunt of the pandemic’s shocks and outgrowths. In India, for example, over 44% of informal workers were jobless in April 2020, suffering more losses than formal workers. In urban slums like San Roque in the NCR, dissatisfaction with government relief precipitated violence and arrests in April 2020. In the Philippines more widely, the militarization of the pandemic response has varied in space and by class. To be sure, the pandemic has made divisions in urban citizenship plain to see — and not exclusively in the Global South. Cities are charged with making sure that they avoid these trappings, that those who may feel insincerely in the city but not sincerely of it, those who may feel helpless and powerless to affect their urban environment, are heard. The stakes are significant: unevenness in the experience of urban citizenship may, for example, create conditions in which accounts of populist sincerity can take root, be corroborated, and become social fact.

Implications?

These are just five of the many signals of change we are experiencing today. While not all are drivers of change at global level, they are the ones we care about and are prioritising in our work with cities and regions to create transformative strategies. To steer city planning towards a regenerative future and help planners build meaningful relationships with their citizens, we have identified (and work in) four impact areas for cities in transition.

Finances

We are rethinking about the financial models that will drive place making. There is a need to find ways to invest in non-commodified values that generate positive externalities and spillovers within city districts. This is about investing in citizen-led initiatives by:

- building relationships with local associations, the private sector and street-front business to upgrade public spaces for contemporary lifestyles

- creating a shared narrative of digitalisation that is understandable and meaningful for citizens.

- Developing mechanisms and processes to constantly engage with the public in utilizing digital assets.

New Models for Futures

Reimagining the future of cities starts from establishing a new mental model to think about societal change. This means avoiding trend-based scenarios in favour of social imagination and building solid alliances, and having experimentation at the forefront of this process. In cities it is about rekindling a much needed public debate, one that is understandable and meaningful for citizens. It is also about equipping policy makers simply with a clear narrative to reach their audience.

Monitoring

The Smart City has produced a great wealth of technologies and data to monitor urban fabric and service delivery. However, in the past few years, we have focused overly on system efficiency and big data to monitor and solve the evolution of urban change. After COVID, city managers will face the need to shift from system-oriented KPIs to people-oriented KPIs. This means using smart city solutions less to monitor how the city performs, and more how their citizens feel about the urban environment. This doesn’t mean tracking people’s digital traces even more than today, but rather collecting and analysing socially relevant datasets.

Wellbeing

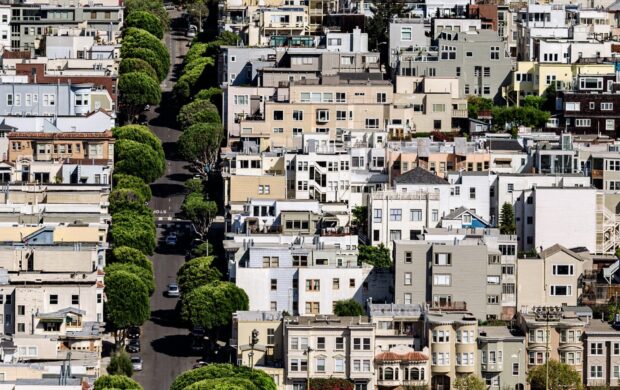

Cities are a major driver behind the decline of biodiversity and they also urgently need to increase the space dedicated to infrastructure for health and wellbeing. In past decades, we prioritised system and service optimisation over the wellbeing of our citizens. Now it is time to convert the space occupied by obsolete infrastructures and urban spaces dedicated to private vehicles into places for increased biodiversity and physical activity. This can have a rapid positive impact on public health and improves the biodiversity and resilience of the city, while also improving its visual outlook.

Authors:

Damiano Cerrone, Consultant at Demos Helsinki and John Hadaway, partner at SPIN Unit

Read next:

- The instant city: how the desire for speedy gratification is reshaping our urban lives Professor Peter Madden, OBE, explores how the pandemic has accelerated another kind of 15-minute-city, where everything can be delivered almost instantly to your door.

- Governance – the overlooked route to transformation: How can we best organise for change? What are the current governance approaches and ways of organising that are being used in attempts to create systems change? What would more systemic governance approaches for our work look/feel like and how might we transition to these?

Join discussion