First published in “After Shock: The World’s Foremost Futurists Reflect on 50 Years of Future Shock and Look Ahead to the Next 50” by John August Media 2/4/2020.

Who makes the future?1

Living in the future is not all it’s cracked up to be. That might surprise Toffler2 because many of his predictions have come true.

Since the publication of Future Shock in 1970 we have seen great advancements in technology but many of the problems of that era, such as economic inequality, have in fact worsened. In his book, Toffler took multiple forms of inequality as a given, and structured his visions of the future without really questioning it. To fully understand the present-day implications of future shock, we have to challenge these assumptions.

Toffler thought the world was structured into three different classes. 70% of people live in the past, over 25% of people live in the present, and 2-3% live in the future3. People who live in the past are based in traditional societies, living the same life that their parents and grandparents did. People in the present live in modern industrial societies, and are “molded by mechanization and mass education.” People living in the future comprise a small portion of the population. They live in the main urban centers of global and technological change, and are wealthy, well-educated, and mobile.

To a modern reader, living in the future seems to be another way of saying “is a highly privileged member of society”. Based on the examples given, it is implied that the people who live in the future are mainly cisgender, white, hetero, wealthy, able-bodied men without any caregiving responsibilities4. They are able to thrive in global urban centers, and withstand a rapid pace of change – one that would unsettle other types of people. The rest of us, who are not living in the future, are doomed to live in a state of “future shock” where we experience the fast pace of technological, social, and economic change, but are helpless and overwhelmed as familiar structures shift around us. As society evolves, a feedback loop is created, as those people with economic and technological power create tools and systems that benefit people like themselves.

I see future shock as one outcome of a broken economic system that produces miraculous technology but fails to prioritize fundamental human needs and values. What makes people anxious, overwhelmed, and unable to weather change, both then and now, is not the historical transition from industrialism to post-industrialism. It is a deep malaise related to a hostile world that still fails to provide enough food, shelter, and security to millions of people. Young people can see how much suffering remains; that society can produce incredible gadgets but not produce solutions to real problems. Who your parents were, your skin color, and the school you went to still play an outsized role in your ability to succeed in this future. Indeed, in some parts of the world, this is even more true than it was in Toffler’s time.

Who wants this future?

One of Toffler’s examples of a person “living in the future” is a Wall Street executive named Bruce Robe who works in New York City and whose family lives in Columbus, Ohio.

Every weekend he boards a jet and commutes home. This example is meant to showcase the impressiveness of jet travel and the rise of a global nomad class. However, we never see the human costs of such opportunities. Is this the world this man wants to live in? How does he feel not seeing his family? How do his wife and children feel about his long absences? Does this future work for them?

For Toffler, it was easier to imagine quick-fix technical interventions that shape the future (the jet), rather than investigating the structural issues that gave rise to the problem in the first place (liveable cities). Toffler did not at the time anticipate the environmental impact caused by jet travel or the social impact of long-distance commuting.

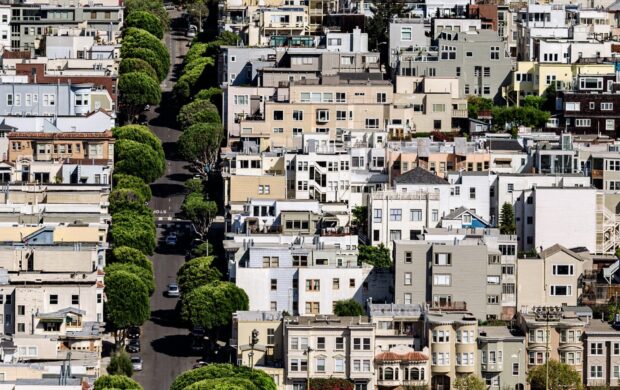

We could imagine a different scenario, one where an improved future for the executive and his family might include affordable housing in a safe and family-friendly New York City. Or perhaps economic opportunities would be more evenly distributed across the country and he could find employment in the thriving business community of Columbus.

In another section, Toffler discusses the future of human reproduction. In his vision, biotechnology could enable women to first pre-select an embryo and then use a mechanical womb in a lab to incubate the baby until time of birth. Here, again, it is unclear who actually wants this future. While some women might find childbirth unpleasant enough to warrant this solution, it doesn’t seem like a widespread problem compared with the reality of raising children in a heavily gendered and unequal society without any childcare support. What use is a mechanical uterus if a parent still cannot access affordable childcare?

Once again, technological solutions seem the most feasible. Universal childcare would require a revaluing of caregiving work. Caregiving work, both then and now, is done predominantly by women, people of color, and immigrants. It isn’t seen as prestigious, nor is it well compensated. It seems easier to most people to invest in a technological solution rather than changing the way we structure our society. Planners and futurists traditionally don’t focus on this topic primarily because it isn’t seen as futuristic, despite childcare providers being a group of people constantly immersed in raising future generations.

Who broke the future?

We still live in a world where not everyone can live in the future. Historically, lots of key groups were left out of visions of the future. Though this is now changing, there is still work left to be done to ensure that diverse views of the future are heard. When people are excluded from creating the future and seeing themselves in the future, they are often forced to claim space for themselves using whatever tools they can access. This can take many forms including revolutions, violence, disengagement, mass exoduses, and suicide.

Millennials in the US (like myself), are economically worse off than their parents, and simply cannot afford some of the basic elements of life in the future (for example, houses and savings accounts).5 The future we inherited is more polluted, more unequal, and more precarious than the world our parents enjoyed. Through the lens of Future Shock it would be easy to proclaim that what is needed is adaptation to the new reality and acceptance of change. However, it seems unfair to blame an entire generation for failure to adapt to the future in a broken world of climate change, growing nationalism, and rising economic inequality.

Who can change the future?

For the past 50 years our world has incentivized and valued technological fixes but has not invested in tackling fundamental issues of equality or forging a sustainable path forward. That underlying structure of inequality has shaped the future and caused the problems we see today. We have failed to take action on critical issues, such as climate change. Rather than restructure our businesses and societies around planetary boundaries, we hope that scientific innovation and geoengineering will bail us out.

The people who have been excluded from living in the future are the people who are most impacted by inequalities today. We need to center their voices as they have the ability to lead grassroots movements that can change the existing system.

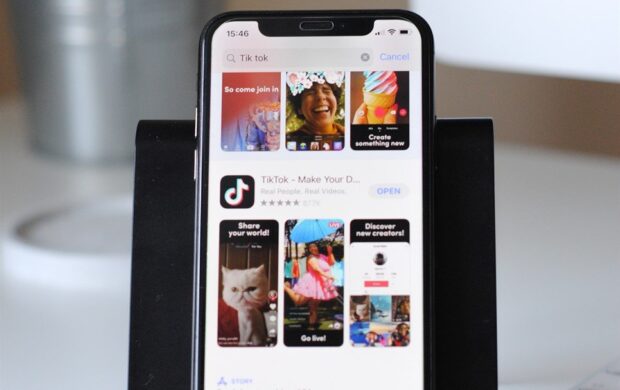

Around the world, young people are striking for climate justice and for their governments to decarbonize. Groups such as Black Lives Matter fight against systemic racism. People are fighting for their right to clean water, healthcare, and a living wage. Citizens are pushing back, governments are changing, and norms are shifting. This is happening because people being traditionally denied a share in the future are fighting for a future vision that is intersectional, sustainable, and equitable.

Young people want to fix the system, starting with core values: a thriving environment, investment in future generations, and the dismantling of structures like colonialism and white supremacy. Futures tools should be used to facilitate this shift, to challenge assumptions of what the world can be, and to make sure we aren’t applying solutions that only benefit a small group. One way they can continue to do so is by helping out thinking go deeper. Only by interrogating the “why” behind the way things are can we figure out the “how” for the way things could be.

But power never concedes without a fight. Fossil fuel companies continue to control major parts of the world economy, right wing nationalism is spreading across the world, older generations are voting for candidates who vow to undermine civil society, and multinational corporations are buying up the world’s water. It can feel as if we are living out our last days on a dying planet. I don’t know if we will be able to adequately address the problems we face, but it is no longer possible to naively assume these problems will go away on their own.

Fixing everyday futures

Popular conceptions of futuristic space colonies and dazzling new technology ignore structural societal problems. They also ignore the mundane ways in which the future often plays out. Even the 2% of people “living in the future” don’t spend a lot of time thinking about the future, as modern technology quickly becomes routine. Humans are and will be concerned with the same things that have always concerned us – basic needs, love, community, and simply getting through each day.

For me, a future that honors and values the mundane lived experience of the billions of people of the world is a better vision. If we can imagine life on Mars, we can imagine a functioning economic system that treats people with dignity. I think that future generations will look back at our world today in shock, that we let things get so bad and that it took so long for us to build a sustainable and equitable world.

Read next:

What Does It Mean to Decolonize the Future? by the Diaspora Futures Collective

Is the future still female? by Joy Green

Reading the waves: who’s making sense of narrative change? by Anna Simpson

1 Thank you to Mark Egerman, Francesca Chubb-Confer, and Anna Warrington for providing feedback on this piece.

2 In this piece I refer to the author of Future Shock as Alvin Toffler. However, although she wasn’t listed as a co-author, futurist Heidi Toffler contributed significantly to the writing of the book.

3 Interestingly Toffler’s math doesn’t add up. It is unclear if the missing 2-3% are in a separate category of people or are omitted to indicate a small buffer.

4 Toffler writes “by comparison with almost anyone else, white Americans and Canadians are regarded as hustling, fast moving go-getters” p 41

5 Millenial home ownership remains significantly lower than other generations – source article

Join discussion